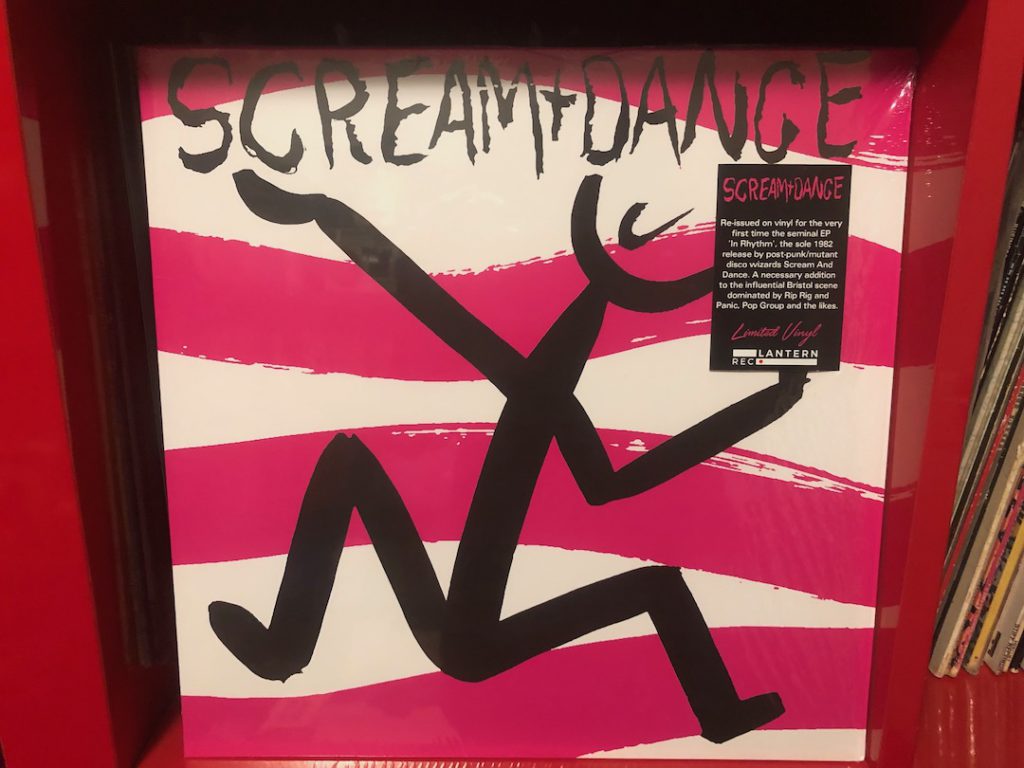

I’m standing by a bin of records at Rubycon, talking to a friend, who also happens to be one of the DJs for an in-store event happening that day. She asks what records I pulled and I flip through the small stack of vinyl that I will soon purchase. I show off a 12” with wavy pink stripes and a large stick figure on the cover. The band’s name, Scream + Dance, is scrawled above the stick figure’s head in thick letters.

I already have digital copies of three out of four tracks on the 12”, thanks to a Recreational Records compilation I found on Bandcamp over a year ago. The EP that I’m holding, though, is a reissue of Scream + Dance’s only release, a slice of the early 1980s intersection of punk, funk and dub that hid in obscurity for decades. It’s great stuff and I tell my friend that. Recommended if you like Delta 5 and The Slits, I add, knowing that she does like both bands. Then I realize that I sound like a music discovery algorithm, albeit one that, hopefully, makes better recommendations than Spotify. It also hits me that we wouldn’t be having this conversation in our DMs or via text. If we’re talking about records, it’s usually because one (or both) of us is DJing or we’re at a record store.

Twenty years ago, record stores were en route to extinction as digital media proliferated. Today, they are one of the last refuges for the bounty of niche genres and subcultures that fall under the banner of alternative culture. But, this is not an essay about the resurgence of vinyl. Record stores, like so many other small, IRL businesses, face a lot of challenges in our shitshow of a timeline. They need our support, maybe more than ever, because they are crucial to keeping scenes alive as the online tools we’ve relied on for the past two decades fail us.

I arrive at Rubycon while Shock Doctrine, a synthpunk/darkwave band, is playing and a crowd of people spills out onto the sidewalk. At one point, I catch a glimpse of the back of the band through the shop’s front door. Mostly, though, I see the crowd. It’s an enthusiastic one, where the looks range from the classic band t-shirt-and-jeans combo to what I’ll call Liquid Sky casual. You can’t put a generational tag on this scene, partially because there is a range of age groups present, but also because being a weirdo transcends marketing demographics. You either get that Liquid Sky reference or you’re normal.

In its current state, the internet is made for normal people. More specifically, it’s made for advertisers whose targets are normal people, the sort whose vibe shifts with every trending topic. So, even though we have access to a monumental amount of music and information, much of it is buried beneath a pile of garbage so big that once you sift through the ads, memes and other assorted distractions, you’ve forgotten what you were searching for the first place.

In fact, I had forgotten that I wanted to get the Scream + Dance EP on vinyl until this Saturday at Rubycon. When I heard them on that Recreational Records comp- which, by the way, was the first time I heard the band— I made a mental note that their dubby post-punk sound goes best with what I play in my all-vinyl DJ sets. But, at some point, I forgot about it, the way I think many of us forget about even the best of what we hear and see online.

I’m old enough to have developed pretty niche tastes in music before streaming and social media. I could tell you that it was soooo much harder to be a weirdo back then, but that’s not entirely true. I see a flyer in the window of Rubycon and remember how much easier it was to keep up-to-date on shows and dance nights when there were stacks of paper flyers and an L.A. Weekly rack inside every record store in the city.

And it’s a hell of a lot easier to pay attention to music when you’re not endlessly scrolling through feeds dominated by hot takes on a billionaire pop star whose name you could have sworn you blocked three times. Even when the store is crowded and bands are loading and unloading gear, it’s still easier to concentrate on what’s in the bins. I find a Pet Shop Boys 12” that I don’t already have and it’s a song that’s been in my head a lot lately, so I pick it up. Then I spot a Lizzy Mercier Descloux album that I think would make a good birthday present for a friend, so I grab that as well. Finally, I come across the Scream + Dance record and remember why I wanted it and that I have a couple all-vinyl gigs coming up.

Then my friend and I start talking and I tell her about the record. At some point, we mention the Angelyne album that Dark Entries is putting out and the release party that’s coming up. I notice a stack of books on the floor with Cosey Fanni Tutti’s memoir, Art. Sex. Music., on top and recommend that too.

These one-on-one chats with friends about music is really important to keeping scenes going. At one point this did happen online and it still does in some small corners of the web, but it’s less common now that socials are spaces where one is expected to perform life in a game where the stakes are viral-or-nothing. We need real world spaces where we can dig through boxes of music, connect with friends and keep up on what’s happening in our immediate surroundings. All that is to say, support your local record stores. They’re doing a lot more for us than streaming platforms and socials are.

Liz O. is an L.A.-based writer and DJ. Read her recently published work and check out her upcoming gigs.

Related:

HOW TO SUPPORT YOUR LOCAL MUSIC SCENE

“ENERGY: A DOCUMENTARY ABOUT DAMO SUZUKI” PREMIERED IN L.A. AT PHILOSOPHICAL RESEARCH SOCIETY